If you are asked to describe your teacher identity, you may find this difficult to articulate. However, if someone asks you what you think is important to the role of a teacher, you would probably be able to give an answer without too much delay. There is something about a discussion of our own identity that puts pressure on each of us – perhaps for fear of revealing something personal that is then open to be judged by others: I am my own identity; I own my teacher identity.

And yet research into teacher identity (Chong et al, 2011) shows us that this is not fixed, it is open to change and it is an important part of the development of a teacher that our identity evolves and adapts as we learn more and our experiences shape us further.

Our teacher identity is partly formed from cultural and social experiences and shaped from our own engagement with education, as children and into adulthood. Lortie, (2020, p.65) refers to this collection of experiences as an ‘apprenticeship of observation’. There is no other profession in which a person has so much personal and intense engagement with the service prior to joining it. This can be a really positive aspect, but it can also make systemic change very difficult as the status quo is often embedded in those who become teachers, from an early age. Britzman (1986, p443) describes how those entering the teaching profession bring their ‘implicit institutional biographies’ –

the cumulative experience of school lives … which in turn, inform their knowledge of the student’s world, of school structure, and of curriculum. All this contributes to well-worn and commonsense images of the teachers’ work and serves as the frame of reference for prospective teachers’ self-images. (Britzman, 1986, p. 443)

For example, a trainee’s institutional biography may include a childhood in a small rural school, followed by an entrance exam to a secondary school, completed by a university first degree in languages. An acknowledgement of the role the trainee’s own modern foreign language teacher played, in instilling a love of language learning, alongside the trainee’s own aptitude for retaining and recalling vocabulary with a pleasing fluency, has encouraged this trainee to become an MfL teacher. The trainee’s identity narrative might sound like; ‘I am a teacher of languages. I believe all children can learn another language if they are taught well.’ However, this trainee’s experience of ‘all’ children has been limited to date. The trainee’s identity is likely to evolve in a number of ways.

It might be that in the first school placement the trainee experiences the professional joy of engaging children who said they hadn’t previously liked Spanish and is able to recognise the progress children make from varying starting points. Incidents of challenging behaviour are difficult and emotional at first, but with the support of a good mentor, the trainee has looked at trigger points and built in notes to the planning to overcome these. Some relationship building was also important to growing success. In this scenario, the trainee is going into the next placement with a zest for using languages to open up children’s possibilities in life and is already looking for a teaching post in a school very different from the one the trainee knew from childhood. ‘I can be a successful teacher for all children’.

Alternatively, it may be that the trainee has a first placement in a school where language teaching is already exclusive, not by design but by default. Those children who haven’t engaged, or who have been disruptive, are withdrawn and go to the ‘Inclusion room’ during language lessons. The trainee still has to manage some challenging behaviour in the class, which results in discussions about whether this child, or that child would ‘benefit’ from being taught in Inclusion for this lesson too. The trainee has some success with the children that remain, but problems that arise are met by avoidance or reactive actions, rather than being truly solved. This trainee’s identity narrative is now, ‘I am a teacher of all the children who are able to be in my classes’ – note the ableist implication of this sentence. This trainee may even believe themselves to be inclusive, as they are using some strategies to include all the children in the class during the lesson. As a result of the systems within the school, the trainee believes that the best place for the children who are not in the lesson is in the Inclusion room and nothing in the trainee’s institutional biography will create a dissonance with that approach.

In an equally plausible scenario the trainee has been inspired by the education that they have received in their teacher training. Throughout their specialist subject lectures and seminars, the focus has been on the use of the graduated approach to tackle children’s barriers to learning an additional language; a knowledge and understanding of common misconceptions for children’s foreign language acquisition; an ambition to plan creatively to engage all pupils; opportunities to reflect and share ideas, fears and tears. The intention of the course is on success, not stress.

Heading into the first placement in the school where children are withdrawn, our trainee is now feeling uncomfortable with the approach being taken by the school. A persuasive head of department may be convincing of the rationale for the approach, but our trainee’s belief in being an inclusive teacher puts them at odds with the reasoning. ‘I can be a teacher of all children but not within this school’s understanding of inclusion’. The trainee can demonstrate ways to engage all the children in the class. The trainee could ask to take an additional language lesson for the children in the Inclusion room, but this would take confidence and a measure of intrinsic motivation. Great if it is possible, but the chances of success are low and others would be looking for this not to work, so as not to invalidate their own beliefs and reasoning.

The trainee will need appropriate support at this point to avoid becoming disillusioned. However, the trainee spends most time with the teacher mentor, who already often feels defeated by disruptive behaviour in the MFL classes and believes the school’s approach to management by avoidance to be justified, by the Head of Department and senior managers. How can the trainee maintain a burgeoning and positive teacher identity when the ideas and hopefulness are not mirrored or magnified within the placement?

In this instance, the trainee was also in an online group of likeminded trainees, set up by the provider. The trainee’s social media profile allowed regular reinforcement from those succeeding in inclusive classrooms. Conflicting views on ‘how to teach’ from old school friends and family, spoken within social settings, occasionally cause the trainee to wobble, but a good selection of reading and listening (podcasts, audiobooks) allows the trainee to see education with a lens calibrated by teacher identity: I am a teacher of all children.

Small successes in the classroom, such as involving children who haven’t previously liked languages, are built on effective lesson planning; engaging task design; a mutuality in the enjoyment of the lessons; respectful acknowledgement by the class of different starting points, yet with shared goals; and the accessibility of the language used.

The trainee finds this placement frustrating and exhausting, but focusses on the class, with an eye on the future. The placement report reflects a ‘need to develop more trusting relationships with colleagues’ and states that ‘whilst it was good to see the trainee encouraging children who had previously found lessons difficult, it is also important to ensure the more able in the class make good progress.’ The trainee may find this a bit defeating, but hopefully that is only temporary. The trainee understands the need for all children in the class to make progress and will take this development point on board. In discussion with her course tutor, the trainee recognises the victory implicit in the report. With a quiet confidence the trainee reaffirms: I can be a teacher of all children.

If teacher identity is important to creating inclusive schools, then it follows that it must be important for trainee teachers to have opportunities throughout their training and beyond to reflect on how being the teacher they believe themselves to be – a teacher of all children – can make a difference to the teacher they become – an effective teacher for all children. We know that teacher retention is affected by the mismatch between the teacher identity that teachers arrive with and the reality that they perceive a few years into their career. Figures for November 2019, show that 15% of teachers leave in the first year after they have trained and just under a third leave within five years (ONS, 2020).

The Cooper/Gibson (2018) report for the DfE on factors affecting teacher recruitment noted a key component in teacher retention is,

‘the ‘high’ of seeing young people make progress or connect with a subject, such as a lesson that they felt had gone well and where pupils demonstrated that they had understood the content. The attitude of pupils had a large influence on these teachers; where young people were motivated to learn or were enthusiastic, teachers reported that this increased their positivity towards their role. Where there were disciplinary issues, this proved challenging in terms of maintaining an effective lesson, but also created additional workload when communicating with parents/carers and logging behavioural issues on a central system. A small number had enjoyed the challenge of working with pupils with complex behavioural issues, to help support them and make a difference. (Cooper/Gibson, 2018, p19)

Consider this quotation in the light of the trainee’s possible experiences in placement. Who is responsible for whether a child is engaged and makes progress in a lesson, or whether a child displays behaviour that creates a disruption? What makes the difference as to whether a teacher sees this as a barrier or a challenge?

If a teacher was asked whether they should include all children with green eyes in the learning of their class they would be taken aback at the nonsense implied. If the same teacher was asked whether all children with dyslexia should be taught in the classroom, the teacher may think momentarily, recognise the challenges this can sometimes bring for the child in question, but give a resolute yes as their answer. They definitely see themselves as a teacher of children with dyslexia. So what is the tipping point for teachers in relation to meeting need? How can anyone see themselves as a teacher of this child, but not a teacher of that child? Written like this, it is easy to see the discrimination involved. But for many teachers there is a point at which they ‘didn’t come into teaching to feel like this’. This point invariably relates to whether or not they perceive poor behaviour as a reason to notice the need being communicated: whether the teacher recognises that they have the skills to adapt and meet that need, or whether they see the behaviours as disruptive, targeted and personal; unrelated to learning.

Having the adaptable skills to recognise an individual’s need within a lesson (which often applies to a group of children) is important. Too often teachers cite their lack of skills as being a reason that a child ‘cannot’ be taught within their class. These ‘skills’ are perceived to be specialist and relate to specific knowledge of conditions and disabilities. Teachers should always be curious for new knowledge that supports them in their role, but a teacher of all children can teach all the children in the class without specialist knowledge of special educational needs. The specialism required is about learning – how children learn and what interrupts learning – this specialism is called teaching.

Pantić and Florian (2015, p.333) consider ‘the capacity of teachers to reflect on their own practices and environments when seeking to support the learning of all students’ as being one of the factors that is important in promoting an identity for social change. The Ofsted frameworks for schools (2019) and for ITT (2020) both set out the intention to monitor the effectiveness of education for all children, in recognition of the need to do something differently in English schools to impact on the achievement of the most disadvantaged.

It is important for professionals who provide of the education of those new to teaching and mentors who support the learning of trainees to facilitate discussions of teacher identity in relation to the inclusive classroom. Whilst recognising the diversity of institutional biographies amongst trainees and in promoting agency in the development of a teacher self, there is still an obligation to draw attention to a range of knowledge and skills which will enable trainees to see themselves as teachers of all children. There is a strong argument for a ‘pedagogy of becoming’, which enables the mentor and trainee or early career teacher to work together, drawing on the new teacher’s views of education and the foundation of the relationship as ‘meaning-making and professional learning,’ (Velikova, 2019, p 15, cited in Ivanova, 2020, p 37).

As well as through our direct experiences and emotional responses, our teacher identities can also be impacted early on by how others see the role of the teacher. Portrayals of teachers and the teaching profession in films and television, through the media and in books can all affect how teachers see themselves. Too often, good drama is made of teachers not coping with disruptive behaviour or a wide range of abilities within a class. Yet equally, ‘One Show’ type examples of hopefulness, tenacity and professional commitment, in which a teacher has made ‘all the difference’, can be inspiring. Snow and Anderson (2001) discuss a model of distancing and embracement, which is like a push-me/pull-me of identity. Distancing is ‘When individuals have to enact roles that imply social identities that are inconsistent to desired self conceptions’ (p. 229). An example of distancing would be the trainee who had to find ways to comply with the placement school’s exclusion of some pupils from the language lesson, contrary to the trainee’s view of an inclusive classroom. Embracement is ‘a person’s verbal and expressive confirmation of acceptance and attachment to the social identity associated with a specific role’ (p. 233). In this instance, the trainee who finds a ‘good fit’ between the teacher they see themselves being and the teacher they can be within this setting.

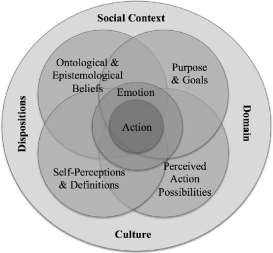

Teacher identity is a complex coming together of beliefs, experience and knowledge. In designing their Dynamic Systems Model of Role Identity (DSMRI), Kaplan and Garner (2017) successfully draw on and combine a number of perspectives on identity from contemporary theorists across disciplines, as well as ‘empirical research on students’ and teachers’ contextual formation of environmental perceptions, self-perceptions, motivation, and action, e.g. choice, investment of effort, self-regulation.’ (Garner and Kaplan, 2019, p 9). The DSMRI presents teacher learning as identity

formation.

Kaplan and Garner embrace the natural factors that impact on teachers and consider the interdependence of circumstances and other factors on a teacher’s identity formation. It is not something that you can get ‘off the shelf’ for example, you cannot guarantee a set teacher identity, if you could just read this, watch that and do this. (Greer, 2020)

The model shows the interdependence of the four main aspects of teacher identity and the factors that impact on them. ‘Like in any other complex dynamic system, change in the teacher role identity is highly dependent on the system’s state and on its environment, which includes the personal and professional contexts in which the teacher lives and works’ (2019 p 10).

Examples of ontological and epistemological beliefs in relation to the inclusive teacher are the beliefs and knowledge that you hold that make you think you should be a teacher of all children. This may include:

However, it is important to recognise the assumptions that you can make as a result of your beliefs and values and how this can bias the thoughts and actions you make.

Your purpose and goals are included in your role identity. Your purpose may be defined as ensuring all children make good progress, but it may include goals that further promote your identity as an inclusive teacher. This may relate to equality and equity, e.g. I will address gender inequalities in my classroom through positive role models within the curriculum and a ‘can do’ approach for all. More concrete goals, objectives, and aims within your role can be specific to an inclusive teacher identity, e.g. regularly reflecting on individual plans to ensure needs are addressed within planning and task design in ways that are appropriate for all.

Exploring your teacher identity with peers and mentors will support the realisation of your teacher self. The closer your teacher self matches your teacher identity the more likely you are to feel a sense of achievement and validation in the role. Finding ways to reflect on your teacher identity throughout your training and beyond can help to recognise the emotions aligned to these purpose and goals, for example, having anxiety about the progress being made by a particular group of children; or excitement in the achievement of some goals more than others. ‘I am ambitious for all children to make progress in my class’ is an identity narrative that evolves from purpose and goals.

Lastly, self-perceptions and self-definitions relate to how you feel you are suited to the role of teaching. How you perceive your personality, characteristics and attributes, and how you feel they are relevant and influential to your teacher identity. As with the previous areas, the emotions which you attach to these self-perceptions and self-definitions are an important factor, e.g. feeling necessary or valued by others; feeling angry about unfair disadvantage. This all helps to shape your identity as an inclusive teacher.

Self-perception also relates to the behaviours you associate with the role of a teacher and the range of behaviours you understand to be acceptable to carry out that role successfully, such as how you respond to incidents of behaviour, what you do when you hold a conflicting opinion to a colleague, how you express joy about learning in the classroom. This can be another way in which teacher identity can mismatch with teacher self, so it is important to be aware of the potential impact when your behaviour doesn’t match your self perceptions and how you can mediate that, or keep your response proportionate and positive.

A teacher identity is a complex business. Being ambitious for the teacher you want to be, exploring how this identity has been formed, being honest about the teacher you think you are, and being open to how you can develop your skills and knowledge to become your desirable teacher self requires determination, reflection and collaboration. To develop an identity as a teacher of all children whilst in training for teaching is a powerful tool for future success. Believe in your own expertise as a teacher of all children, whilst drawing on the experience and opinions of co-experts;

colleagues, parents and carers, the child, SENDCo, therapists and psychologist.

Be brave; be hopeful; be resilient and be curious. You can be a teacher of all children.

Julie Greer February 2021

Britzman, D. P. (1986). Cultural myths in the making of a teacher: Biography and social structure in teacher education. Harvard Educational Review, 45(4), 442-456.

Chong, S, Low E L, & Goh K C (2011). Developing student teachers’ professional identities: An exploratory study. International Education Studies. 4:1. pp 30-39. Ontario: CCSE. Available at eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1066392 (accessed 25 June 2020)

Cooper, Gibson Research/DfE (2018) Factors Affecting Teacher Retention. Available at: assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/686947/Factors_affecting_teacher_retention_-_qualitative_investigation.pdf (accessed 12 February 2021)

Garner, J and Kaplan, A (2019) A complex dynamic systems perspective on teacher learning and identity formation: an instrumental case Teachers and Teaching, 25:1, pp 7-33 London: Routledge. Available at www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13540602.2018.1533811 (accessed 26 February

2021)

Greer, J (2020) Workload: Taking Ownership of Your Teaching. St Albans: Critical Publishing

Ivanova, I, 2020, Strengthening teacher identity and professionalism as a way to increase the appeal and status of teaching profession. Studies in Linguistics, Culture and FLT. 6. ResearchGate. Available at www.researchgate.net/publication/341265969 (accessed 12 June 2020)

Kaplan, A., & Garner, J. K. (2017). A complex dynamic systems perspective on identity and its development: The Dynamic Systems Model of Role Identity. Developmental Psychology, 53:11, 2036-2051. DOI: 10.1037/dev0000339 (accessed 28 February 2021)

Lortie, D.C, 2020, Schoolteacher: A Sociological Study. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Office for National Statistics (2020), School workforce in England: November 2019. London: HMSO. Available at https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-workforce-inengland (accessed 25 February 2021)

Pantić, N and Florian, L (2015) Developing teachers as agents of inclusion and social justice. In Education Inquiry, 6:3 27311. Abingdon: Routledge. DOI: 10.3402/edui.v6.27311 (accessed 27 February 2021)

Snow, D. & Anderson, L. (2001) Salvaging the self, in: A. Branaman (Ed.) Self and society. Oxford: Blackwells.